By Gene Luen Yang

By Gene Luen Yang

240 pages, color

Published by First Second Books

A couple of years ago, Gene Luen Yang began to release segments of American Born Chinese as mini-comics. I’d remembered his work from comics like Gordon Yamato and the King of the Geeks and Duncan’s Kingdom and that was enough to persuade me to give this new project a try. At the time, I remember thinking that I had absolutely no idea where this was going, and was more than a little unsure of it as a whole. Now that the book is complete and published as a single unit, my only real question is why I’d ever doubted him in the first place.

In ancient China, the Monkey King is desperate for recognition by the other deities who refuse to see him as anything but a monkey—so he decides it’s time to prove them all wrong once and for all. Jin Wang is a modern-day kid who moves to a new town and discovers that it’s not easy being the only Chinese-American student at your school. And Danny is your typical high school basketball player whose life is perfect every year until his cousin Chin-Kee comes to visit from China, forcing Danny to change schools in an effort to escape the stigma attached to him as a result. They’re three very different lives—but they’re all wanting the exact same thing.

In ancient China, the Monkey King is desperate for recognition by the other deities who refuse to see him as anything but a monkey—so he decides it’s time to prove them all wrong once and for all. Jin Wang is a modern-day kid who moves to a new town and discovers that it’s not easy being the only Chinese-American student at your school. And Danny is your typical high school basketball player whose life is perfect every year until his cousin Chin-Kee comes to visit from China, forcing Danny to change schools in an effort to escape the stigma attached to him as a result. They’re three very different lives—but they’re all wanting the exact same thing.

Yang’s American Born Chinese is one of the stronger examples of multiple, intertwined narratives that I can remember. Each of the three threads—the Monkey King, Jin, and Danny—stands on its own initially as its own, independent story. It’s not until we get to the end of the book that one sees how the plots of the three are connected, doing so in a fairly delightful manner. None of the stories feel like they’re getting short shrift from the others, and that balance between the narratives helps keep the reader interested in all three. At the same time, it’s clear from the beginning that the three stories are connected when it comes to the themes of identity and acceptance. All of our main characters are desperate to shed something connected to themselves—the Monkey King’s species, Jin’s Chinese heritage, and Danny’s cousin—for the sake of how other people perceive them. Yang neatly sidesteps the chance for this to become a story that preaches or speaks condescendingly to the reader, though. The basic theme is stated quickly and then left in the background for the reader to think about; while the basic idea permeates the book, one never feels like Yang is hitting you over the head with the ideas.

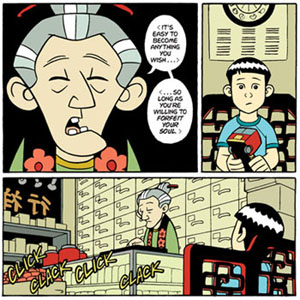

Strong storytelling aside, the characters in American Born Chinese are who will keep the average reader’s interest attuned to the book. It’s hard not to feel sympathy for each of our three protagonists, even though they’re all coming from very different places. The Monkey King’s early dismissal by the other deities stings in its rude (if truthful) nature, and you want him to succeed and show the other deities his own worthiness as a direct result. Yang has a fun time retelling the Chinese fable of the Monkey King here, keeping a light level of humor attached to his story as he explains the different disciplines that the Monkey King learns, as well as the Monkey King’s sharp tongue and jokes that crop up throughout his narrative. Where the Monkey King is self-assured and looking for revenge, though, Jin resonates with readers for different reasons as he desperately tries to get validation from a peer group that’s uninterested in his presence. Jin’s life changing after he leaves San Francisco is hard to not sympathize with. It’s a very typical story of a kid being bullied by the others at his school for being different, but it’s told with real heart and honesty that gives it a nice emotional punch. In particular, Jin’s relationship with his friend Wei-Chen stands out for its realism and how much it says about Jin as a person. Yang isn’t afraid to show Jin’s issues with his own heritage and identity by having him take them out on Wei-Chen, and by not keeping Jin a perfect or ideal character makes him all the more interesting.

Strong storytelling aside, the characters in American Born Chinese are who will keep the average reader’s interest attuned to the book. It’s hard not to feel sympathy for each of our three protagonists, even though they’re all coming from very different places. The Monkey King’s early dismissal by the other deities stings in its rude (if truthful) nature, and you want him to succeed and show the other deities his own worthiness as a direct result. Yang has a fun time retelling the Chinese fable of the Monkey King here, keeping a light level of humor attached to his story as he explains the different disciplines that the Monkey King learns, as well as the Monkey King’s sharp tongue and jokes that crop up throughout his narrative. Where the Monkey King is self-assured and looking for revenge, though, Jin resonates with readers for different reasons as he desperately tries to get validation from a peer group that’s uninterested in his presence. Jin’s life changing after he leaves San Francisco is hard to not sympathize with. It’s a very typical story of a kid being bullied by the others at his school for being different, but it’s told with real heart and honesty that gives it a nice emotional punch. In particular, Jin’s relationship with his friend Wei-Chen stands out for its realism and how much it says about Jin as a person. Yang isn’t afraid to show Jin’s issues with his own heritage and identity by having him take them out on Wei-Chen, and by not keeping Jin a perfect or ideal character makes him all the more interesting.

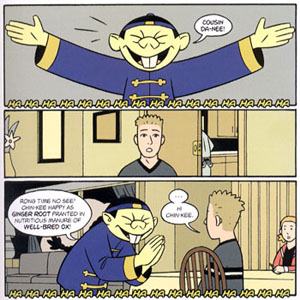

It’s hard to ignore what for some may be the most controversial part of American Born Chinese, namely the story of Danny and his cousin Chin-Kee. Chin-Kee is portrayed as the ultimate negative stereotype of a Chinese person, from traditional ancient Chinese clothing and an unrealistic yellow coloring (which no other Asian characters in the book have), to horrible buck teeth and an accent that substitutes all R sounds with an L. Ignoring that Yang himself is Chinese-American, it’s certainly understandable why he’s doing this; Chin-Kee is supposed to be Danny’s nightmare, everything that he hates about Chinese heritage in general. It’s certainly meant to provoke, to disturb, and to annoy the reader. Does Yang succeed? Absolutely. It’s also an outward manifestation of all of the racism that some of the characters in American Born Chinese display, both spoken and otherwise. It makes Danny a more interesting character, because you simultaneously have pity for him being saddled with Chin-Kee, even as Danny’s embarrassment and disdain for his cousin make him a little tarnished and not entirely able to be sympathetic for his own specific faults coming to life in such a way. It’s a fine balance that Yang strikes, and the character does everything that Yang intends it to accomplish.

It’s hard to ignore what for some may be the most controversial part of American Born Chinese, namely the story of Danny and his cousin Chin-Kee. Chin-Kee is portrayed as the ultimate negative stereotype of a Chinese person, from traditional ancient Chinese clothing and an unrealistic yellow coloring (which no other Asian characters in the book have), to horrible buck teeth and an accent that substitutes all R sounds with an L. Ignoring that Yang himself is Chinese-American, it’s certainly understandable why he’s doing this; Chin-Kee is supposed to be Danny’s nightmare, everything that he hates about Chinese heritage in general. It’s certainly meant to provoke, to disturb, and to annoy the reader. Does Yang succeed? Absolutely. It’s also an outward manifestation of all of the racism that some of the characters in American Born Chinese display, both spoken and otherwise. It makes Danny a more interesting character, because you simultaneously have pity for him being saddled with Chin-Kee, even as Danny’s embarrassment and disdain for his cousin make him a little tarnished and not entirely able to be sympathetic for his own specific faults coming to life in such a way. It’s a fine balance that Yang strikes, and the character does everything that Yang intends it to accomplish.

Yang has a beautiful, simple art style in American Born Chinese. It’s a very clean look for the book, drawing the characters with a minimum of crisp, clear lines. There’s a real care to the look and feel of the story, with as much care paid to the backgrounds and settings of each scene as to the characters that inhabit them. Each page works well as an individual unit, carefully composed and originally drawn in the dimensions of a square. It’s impressive how well each page fits together, with the flow moving from panel to panel easily, and everything from colors to lettering carefully selected to work as part of the greater whole. Yang seems to especially have fun with drawing the Monkey King sequences, which between the kung fu attacks and the elaborate looking demons gives him a real chance to show off his creativity and imagination. It’s a nice break from the reality of the other two storylines, while at the same time maintains the same basic visual style that Yang carries from one character’s thread to the next.

Yang collaborated with Derek Kirk Kim on the comic Duncan’s Kingdom some time ago, with Kim soon after having a break-out hit in the form of Same Difference and Other Stories. This, then, is Yang’s own break-out project; if this doesn’t put him on the map in comics and give him the attention that he rightfully deserves, I don’t know what will. Beautifully written and drawn, and coupled with extremely high production values from publisher First Second, American Born Chinese is a fantastic book from start to finish. Highly recommended.

Purchase Links: