By Lynda Barry

By Lynda Barry

208 pages, color

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

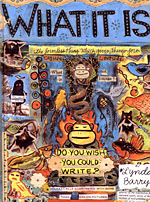

One of my favorite books published in 2002 was Lynda Barry’s One Hundred Demons, as Barry told stories of her past in an attempt to exorcise those demons. In doing so, her observations on a lot of parts of life had really resonated with me, bringing up those emotions and ideas that I’d been carrying around for years as well. In her first original graphic novel, What It Is, Barry plumbs her early life again as she tries to understand imagination and creativity and how it works. The end result is perhaps one of the most necessary books of 2008.

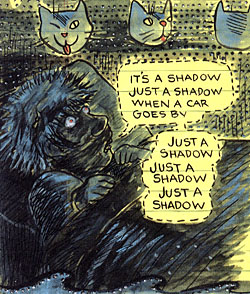

What It Is is several different books in one. The most prominent feature of the book is Barry telling her own story, about the games she played as a child, her experience with art classes, the effect her home life had on how she viewed the world, and more. That part alone is worth the cover price of the book, easily, and it’s the easiest part of What It Is to fixate on. Interwoven throughout this narrative, though, are full page questions, massive collages that ask a question and are then a combination of Barry giving some of her own ideas to the answer, as well as asking more questions at the same time. “Where/why do we keep bad memories?” “What happens when we read a story?” “What is the difference between awake and asleep?” My initial inclination upon seeing these was to skip them, and no doubt go through the book later and examine them. I was maybe about 20% of the way through the book when I stopped and looked at one of them really closely. Then I went back, and started the book over. In some ways these are part of the narrative, these “essay questions” that that Barry asks. So much of What It Is involves getting inside Barry’s head, and these creations of paint and clippings and stamps come together in a way that a simple written answer never could have conveyed.

What It Is is several different books in one. The most prominent feature of the book is Barry telling her own story, about the games she played as a child, her experience with art classes, the effect her home life had on how she viewed the world, and more. That part alone is worth the cover price of the book, easily, and it’s the easiest part of What It Is to fixate on. Interwoven throughout this narrative, though, are full page questions, massive collages that ask a question and are then a combination of Barry giving some of her own ideas to the answer, as well as asking more questions at the same time. “Where/why do we keep bad memories?” “What happens when we read a story?” “What is the difference between awake and asleep?” My initial inclination upon seeing these was to skip them, and no doubt go through the book later and examine them. I was maybe about 20% of the way through the book when I stopped and looked at one of them really closely. Then I went back, and started the book over. In some ways these are part of the narrative, these “essay questions” that that Barry asks. So much of What It Is involves getting inside Barry’s head, and these creations of paint and clippings and stamps come together in a way that a simple written answer never could have conveyed.

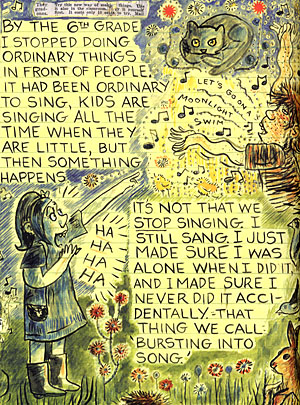

The story itself is, honestly, a little disturbing in places. Maybe it’s because it’s easy to see our own defeat in parts of Barry’s story, the way that creativity is so often beaten down by others or even by ourselves. Barry talks about how she stopped doing things like bursting into song around other people, that sudden moment of being self-conscious about the way that others look at us. “It’s not that we stop singing,” she notes. “I still sang. I just made sure I was alone when I did it, and I made sure I never did it accidentally.” And really, how many other people are in that same boat? Barry believes it happens to most of us, still singing but secretly and all alone. And it’s easy for most readers, I suspect, to see that in themselves.

The story itself is, honestly, a little disturbing in places. Maybe it’s because it’s easy to see our own defeat in parts of Barry’s story, the way that creativity is so often beaten down by others or even by ourselves. Barry talks about how she stopped doing things like bursting into song around other people, that sudden moment of being self-conscious about the way that others look at us. “It’s not that we stop singing,” she notes. “I still sang. I just made sure I was alone when I did it, and I made sure I never did it accidentally.” And really, how many other people are in that same boat? Barry believes it happens to most of us, still singing but secretly and all alone. And it’s easy for most readers, I suspect, to see that in themselves.

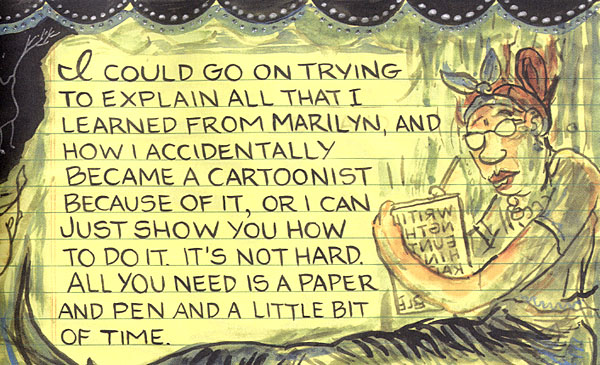

At the same time, though, Barry uses What It Is to show how she got herself out of that cycle of doubt and self-defeat in her art. There’s a section where she’s continually questioning herself, the art having shifted from lush painted pages on yellow legal pads, to a simple thin pen line on a white page, full of muted greens and Barry’s own demons mocking her for being able to answer the two questions she continually asks herself about her art (“Is this good?” “Does this suck?”). And then, as she finally answers the question, everything shifts back to its original style. It’s a visual trick that others have used as well, of course, but that doesn’t make it any less dramatic or appealing here. It’s almost as if we’re hearing Barry exhale as that final tick forward occurs, answering a puzzle that she notes she’ll forget she’s solved before and have to go through again and again. But in that moment, as Barry not only gives her sudden moment of clarity to the reader but explains it in context with her earlier statements on creativity and quitting, it’s hard to not be completely enchanted by What It Is.

The last third of What It Is, once it has finished urging people to rediscover their own creativity once more, turns into two manuals on doing just that. It’s not a narrative here, but Barry’s discussions on how to get your project rolling and ways to recognize your own imagination very much feed into everything she’d said in the book up until then. It’s the sort of thing that you should read even if you aren’t planning on working on your own creative project, just so that you can have some of those long-dormant sparks in your own head again.

What It Is‘s strange blend of workbook, narrative, and existential essay doesn’t feel like anything else out there, but in the best possible way. Barry’s art is at its most expressive and open here, and it’s hard to not just keep reading and re-reading it. (In the space of a week I’ve already read it five times.) If What It Is doesn’t top a number of best-of lists at the end of the year, I will be shocked. Buy this book, buy this book, buy this book.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com