Edited by Chris Pitzer

Edited by Chris Pitzer

192 pages, two-color

Published by AdHouse Books

Robots and space have always been two hallmarks of the future. In movies, television, books, both of them evoke a sense of wonder and awe, in the idea of what we might find out in space, as well as what we might be able to create ourselves in robots. When AdHouse Books announced Project: Telstar (a “spacial robotic anthology”) as its third publication, I knew we’d get high production values and a slick-looking final product. Happily, not only was this the case, but editor Chris Pitzer made sure to round up an incredibly strong group of contributors to boot.

Project: Telstar contains a wide variety of contributions, all dealing with space or robots in one form or another. Comedies about robot dates, dramas about floating to the end of the universe, and all points in-between are collected here; portfolios of skateboarding robots and Victorian-era styled inventions fill the gaps, moving you seamlessly from one to the next. As an added bonus, all contributions also use a metallic blue ink as a second color in the book, giving stories an added gleam of technology and excitement to them.

Project: Telstar contains a wide variety of contributions, all dealing with space or robots in one form or another. Comedies about robot dates, dramas about floating to the end of the universe, and all points in-between are collected here; portfolios of skateboarding robots and Victorian-era styled inventions fill the gaps, moving you seamlessly from one to the next. As an added bonus, all contributions also use a metallic blue ink as a second color in the book, giving stories an added gleam of technology and excitement to them.

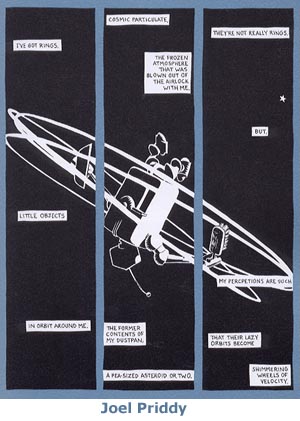

It’s hard to pick favorite stories in a book with so much talent on display, but the real winners have to be the contributions by Paul Hornschemeier, Joel Priddy, and Mark Burrier. Hornschemeier’s “We Were…” and Joel Priddy’s “Long Slow Flight…” both examine the idea of robots’s drive to continue until their fuel is exhausted, but each tackle the subject from a different angle. Hornschemeier’s story is a beautiful tragedy, looking at its protagonist move through the sand towards a destination it may never reach. With his soft lines and gentle cursive script, there’s an old-fashioned elegance on display in this story’s execution. It’s a story that can take the time to focus on a knee joint or a handful of grains of sand and still keep the reader’s attention with the greatest of ease.

That’s also true of Priddy’s story of a robot drifting through the universe, using starlight as a meager source of fuel. It’s fascinating to read Priddy’s narration of aeons passing in the blink of an eye, making such a long-spanning story feel so close and personal. The nine panel grid that Priddy uses is gorgeous in its simplicity, able to denote the movement of time and space as everything from robots to galaxies shift across its framework. Priddy wisely keeps the metallic ink to the panel borders here, letting the pure black and white art speak so much to the reader up until the final moment. Burrier’s story “Piano Music” is on a much smaller scale but no less important. Burrier is able to speak of desire, here, both in what we do and do not want in our lives. Burrier’s interpretation of the theme of space is handled very differently here than in any of the other stories, but no less effectively. It’s a very down to earth and personal story that I think anyone who has loved will easily understand.

That’s also true of Priddy’s story of a robot drifting through the universe, using starlight as a meager source of fuel. It’s fascinating to read Priddy’s narration of aeons passing in the blink of an eye, making such a long-spanning story feel so close and personal. The nine panel grid that Priddy uses is gorgeous in its simplicity, able to denote the movement of time and space as everything from robots to galaxies shift across its framework. Priddy wisely keeps the metallic ink to the panel borders here, letting the pure black and white art speak so much to the reader up until the final moment. Burrier’s story “Piano Music” is on a much smaller scale but no less important. Burrier is able to speak of desire, here, both in what we do and do not want in our lives. Burrier’s interpretation of the theme of space is handled very differently here than in any of the other stories, but no less effectively. It’s a very down to earth and personal story that I think anyone who has loved will easily understand.

That’s not to say, of course, that the other contributions aren’t good. There’s not a rotten apple in the bunch, something pretty rare in anthologies of almost any medium. Bernie Mireault’s look at the future brings a sense of alienness to the future, truly making it feel like a very different culture than what we are used to. By way of contrast, Robert Ullman’s story of robots going on dates is much closer to a society that we’re used to, able to use its similarities to help with both its jokes and its ultimate warmth. One of the longest pieces in the book, Gregory Benton’s “Passover” is in many ways one that can hit home the most for readers, showing both a degradation of the world we live in as well as the desire to hold onto it as long as possible. In a time where many people are finding things they love in life getting swept away forever as the world changes around them, it’s easy to understand Benton’s characters and how they have to deal with the idea of saying goodbye to innocence. One could almost use Project: Telstar as a shopping list, making notes to check out more by creators you might have overlooked in the past like Benton, or new talents like Jeffrey Brown.

That’s not to say, of course, that the other contributions aren’t good. There’s not a rotten apple in the bunch, something pretty rare in anthologies of almost any medium. Bernie Mireault’s look at the future brings a sense of alienness to the future, truly making it feel like a very different culture than what we are used to. By way of contrast, Robert Ullman’s story of robots going on dates is much closer to a society that we’re used to, able to use its similarities to help with both its jokes and its ultimate warmth. One of the longest pieces in the book, Gregory Benton’s “Passover” is in many ways one that can hit home the most for readers, showing both a degradation of the world we live in as well as the desire to hold onto it as long as possible. In a time where many people are finding things they love in life getting swept away forever as the world changes around them, it’s easy to understand Benton’s characters and how they have to deal with the idea of saying goodbye to innocence. One could almost use Project: Telstar as a shopping list, making notes to check out more by creators you might have overlooked in the past like Benton, or new talents like Jeffrey Brown.

When the worst you can level against an anthology is that the least of its stories are merely “good”, you know you’ve got a winner. Hopefully Pitzer and AdHouse Books will be assembling this sort of high-quality anthology on an annual basis, because this serves both as a showcase for creators and a strong piece of fiction in its own right.