By Kazuichi Hanawa

By Kazuichi Hanawa

240 pages, black and white

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

When I heard about Doing Time I got really excited. The idea of comic creator Kazuichi Hanawa going to prison for three years (over an illegal private gun collection) and then creating a comic about his experience sounded really intriguing. After seeing sensationalized accounts in the media like HBO’s Oz, or the comic book series Hard Time, this promised to show what the real deal was, at least in Japan. Well, the truth is now out there thanks to Doing Time and let it be known: prison is boring.

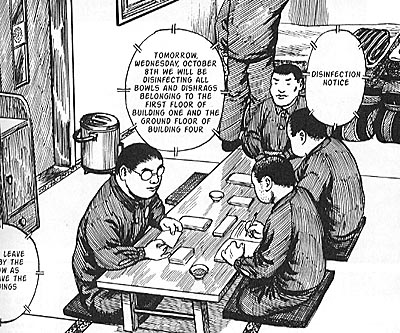

Hanawa’s life in prison is one of monotony and being controlled. Do not turn your head without receiving permission. Do not write in your books. Do not own too many books. Finish your meals. Be prepared for your routine inspection. Do not pick up a dropped tool without asking. Do not exchange contact information. The list goes on and on, and Hanawa shows us in explicit detail what it’s like to live this sort of life. There’s absolutely no confusion on what it’s like to be in prison in Japan, and how the sameness of it day in and day out is enough to drive a prisoner mad. Unfortunately, the same is also true for the reader.

Every now and then Hanawa gives us something interesting, like a theoretical vision into the future where, free from prison, he still finds himself trapped in the same routines and having to beg for permission from others to do the most simple of things. The problem is that these sparks of interest are few and far between, with the majority of Doing Time focusing more on what it’s like to live in prison, down to the most minute detail. Do we really want to know every single meal they ate for several weeks, or every single fold used to construct a paper bag in the prison work program? While Doing Time is a fantastic book for anyone needing to do research on Japan’s prisons so they can get all the details correct, it’s mind-numbing for the reader. Perhaps that’s what Hanawa is trying to get at—a prison sentence is years of boredom for the person being sentenced—but one shouldn’t have to slog through 240 pages to discover this simple fact.

Every now and then Hanawa gives us something interesting, like a theoretical vision into the future where, free from prison, he still finds himself trapped in the same routines and having to beg for permission from others to do the most simple of things. The problem is that these sparks of interest are few and far between, with the majority of Doing Time focusing more on what it’s like to live in prison, down to the most minute detail. Do we really want to know every single meal they ate for several weeks, or every single fold used to construct a paper bag in the prison work program? While Doing Time is a fantastic book for anyone needing to do research on Japan’s prisons so they can get all the details correct, it’s mind-numbing for the reader. Perhaps that’s what Hanawa is trying to get at—a prison sentence is years of boredom for the person being sentenced—but one shouldn’t have to slog through 240 pages to discover this simple fact.

The art in Hanawa, ironically, reminds me a lot of instruction manual illustrations. (“How to Survive in Prison in Ten Easy Steps!”) They’re very clinical, labeling everything in a room from flypaper and mirrors to a garbage can and a tea urn. Once again, Hanawa’s doing a great job of capturing exactly what the interior of a prison looks like, but there’s almost too much detail to keep one interested. There are only so many times you can see Hanawa draw a bowl of rice for it to be interesting, for instance, and most of his people look so nondescript that I had real trouble telling anyone apart. There are exceptions that kept me reading, but they were few and far-between. Having Hanawa clutch his head and moan that his brain is turning to sawdust while we see metaphorical sawdust pour out of his head was amusing, but that’s about the highest point of imagination we get in the art.

In the end, Doing Time was informative and good to read on a “this is knowledge I never had before” level, but in terms of entertainment it just doesn’t deliver the goods. I wanted to like this a great deal, but if to get enjoyment I need to watch the over-the-top Oz DVD sets, well, there are worse fates in life.

Purchase Links: