By Willy Linthout

By Willy Linthout

168 pages, black and white

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

I have to admit that I’ve been sitting on a copy of Years of the Elephant for almost five months now, having read it but not diving into writing a review. As strange as it sounds, it had to do with a sense of respect that I had for the book. Based on Willy Linthout’s own experiences after the sudden death of his son, Years of the Elephant felt like a book that couldn’t be rushed into, couldn’t be taken lightly. After a while, I began to also recognize that some of my delay in writing a review of Years of the Elephant was a small bit of avoidance. And that, more than anything else, felt extremely apt when talking about this book.

Linthout creates Charles Germonprez as his alter ego in Years of the Elephant, a businessman in his 50s living with his wife Simone, whose son Jack has just leapt off the roof of their apartment building to his death. There’s no warning, no sign that this is coming, and Linthout appropriately starts the book with a one-page strip as a typical day is suddenly shattered by the arrival of police at the door bearing the bad news. As Charles is reeling from the shock, we get the title pages and introduction, almost like the opening credits after a teaser on television. In some ways, Years of the Elephant starts with a punch to the gut and never relents from that moment on.

Linthout creates Charles Germonprez as his alter ego in Years of the Elephant, a businessman in his 50s living with his wife Simone, whose son Jack has just leapt off the roof of their apartment building to his death. There’s no warning, no sign that this is coming, and Linthout appropriately starts the book with a one-page strip as a typical day is suddenly shattered by the arrival of police at the door bearing the bad news. As Charles is reeling from the shock, we get the title pages and introduction, almost like the opening credits after a teaser on television. In some ways, Years of the Elephant starts with a punch to the gut and never relents from that moment on.

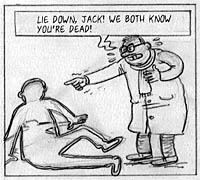

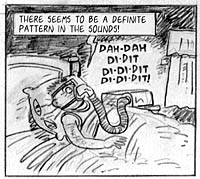

It’s difficult at times to read Years of the Elephant, to see the grief, despair, and even delusions that Charles goes through in the days, months, and years that follow. Jack was Charles’s only son, and the loss quickly turns into a lingering specter that refuses to let go. Some scenes look at first to be played for laughs, as Charles tries to save the the pavement that Jack’s chalk outline was upon, or when the clicking noises of a breathing apparatus are believed to be a message from beyond the grave for Charles.  The laughter, though, is almost a hysterical giggle more than anything else. As Charles goes through what appears to be a series of mental breakdowns, his precarious grip on reality slips bit by bit. What might initially look to be coping mechanisms rapidly turn into dangerous delusions, ones that help Charles avoid the sadness that threatens to overtake him, and as a reader you begin to wonder at what point things will turn back to normal for Charles. Except, of course, in some ways that’s the big message of Years of the Elephant; it will never be "normal" again for Charles. The suicide of his only child is most likely going to haunt him for the rest of his life, even if the degree to which it does so might change over time.

The laughter, though, is almost a hysterical giggle more than anything else. As Charles goes through what appears to be a series of mental breakdowns, his precarious grip on reality slips bit by bit. What might initially look to be coping mechanisms rapidly turn into dangerous delusions, ones that help Charles avoid the sadness that threatens to overtake him, and as a reader you begin to wonder at what point things will turn back to normal for Charles. Except, of course, in some ways that’s the big message of Years of the Elephant; it will never be "normal" again for Charles. The suicide of his only child is most likely going to haunt him for the rest of his life, even if the degree to which it does so might change over time.

One of the most interesting aspects of Years of the Elephant for me was the position that Charles’s wife Simone has within the book. We see her in the first panel of the book, vacuuming the floor with an old canister machine, her face in profile and mostly hidden by hair. On the second panel she’s halfway out of view, stepping beyond the border even as there is an ominous "thud" sound outside. And then, from that point on, she’s gone, forever out of view to the reader. All we experience at that point is Simone’s words from off-panel, or once in a blue moon a hand extending into view for a split second. It becomes emblematic of Charles’s losing sight of the one life line he still has left as the idea of any sort of family becomes too painful to contemplate. Even when Charles realizes, finally, that Simone is the one thing he still has left in his life it looks to possibly be too late. The metaphorical chasm that has grown between them bursts into life within their apartment, perhaps impossible to ever cross and repair. It’s a revelation that is left up to the reader to decide the outcome of, even as Linthout lets the book fade from "Charles" to a brief depiction of his own life. It’s an uncertain ending that none the less is extremely fitting for Years of the Elephant.

Linthout draws Years of the Elephant in a slightly-rough, unfinished and uninked state. It’s a deliberate choice on the part of Linthout, mentioned in the introduction as a way to symbolize the life of Linthout’s own son that had stopped before it ever matured. It’s a sad but smart tribute, but perhaps more importantly it works well as a visual style for Years of the Elephant‘s story. With the art consisting of thicker pencil lines over loose pencil roughs, Charles and company look like at any moment their squiggled interiors are going to burst out of their shells and fly away. And for all of Linthout’s cartoonish style, there are moments of real panic hidden within them, from being enveloped by cords to the look of grief on Charles’s face as he tries to communicate with his dead son.

Linthout draws Years of the Elephant in a slightly-rough, unfinished and uninked state. It’s a deliberate choice on the part of Linthout, mentioned in the introduction as a way to symbolize the life of Linthout’s own son that had stopped before it ever matured. It’s a sad but smart tribute, but perhaps more importantly it works well as a visual style for Years of the Elephant‘s story. With the art consisting of thicker pencil lines over loose pencil roughs, Charles and company look like at any moment their squiggled interiors are going to burst out of their shells and fly away. And for all of Linthout’s cartoonish style, there are moments of real panic hidden within them, from being enveloped by cords to the look of grief on Charles’s face as he tries to communicate with his dead son.

Years of the Elephant is a deceptively dark book. A book about the death of one’s son is never going to be light fare, but Linthout drapes a light surface level of frivolity over top his story. The further you go, though, the deeper you sink into the depths along with Linthout’s alter-ego, and the more chilling the book becomes. It’s an honest, unflinching look at the journey of grief over a suicide, and while it’s not an easy book to read, I do highly recommend it. It’s a book that you’ll find hard to forget.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com | Powell’s Books