By Kevin C. Pyle

By Kevin C. Pyle

176 pages, two-color

Published by Henry Holt Books

The split-narrative is a tricky structure to master, as Kevin C. Pyle’s Take What You Can Carry illustrates. Pyle’s book tells two different stories separated by four decades, switching back and forth between the two. In order to pull that off, though, both halves of the book need to be of equal strength. Otherwise you end up with a book like this one, where one half ends up feeling a bit superior to its counterpart.

The two narratives in Take What You Can Carry are of Ken in the 1941 when his Japanese-American family was sent to a relocation camp during World War II, and of Kyle in 1978 soon after moving to a Chicago suburb. While Ken has to deal with his family being treated like animals and losing their entire life, Kyle has to deal with living in a new neighborhood with few friends and trying to figure out life with his father. And if one of these sounds like a slightly more powerful and interesting story than the other, you’d be right.

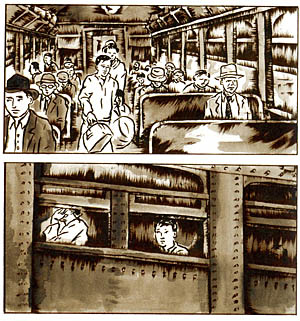

Pyle chooses to tell Ken’s story in a silent format, using sepia ink washes and a gentle style to bring across the demeaning nature of being placed in a relocation camp. It’s a period of American history that is rarely talked about, and I couldn’t help but feel like if Pyle had devoted the entire book to this part of the story I’d have been pleased. I’m not convinced that the silent nature entirely works; there are historical notes given at the back of the book to explain some of what was going on, and I think that might not have been necessary with a little narration or dialogue. But it’s still by far the stronger half of the book; Ken and his family’s struggle to survive is simultaneously heartbreaking and inspirational. In a story where a people’s own country rises up against them, this could have easily gone negatively, but instead shows Ken and his family staying strong in the face of racism.

Pyle chooses to tell Ken’s story in a silent format, using sepia ink washes and a gentle style to bring across the demeaning nature of being placed in a relocation camp. It’s a period of American history that is rarely talked about, and I couldn’t help but feel like if Pyle had devoted the entire book to this part of the story I’d have been pleased. I’m not convinced that the silent nature entirely works; there are historical notes given at the back of the book to explain some of what was going on, and I think that might not have been necessary with a little narration or dialogue. But it’s still by far the stronger half of the book; Ken and his family’s struggle to survive is simultaneously heartbreaking and inspirational. In a story where a people’s own country rises up against them, this could have easily gone negatively, but instead shows Ken and his family staying strong in the face of racism.

Kyle’s story suffers partially in comparison to Ken’s. Unlike Ken, Kyle is certainly not silent, and he’s like so many typical teenagers. He’s brash and rude, and he’s more than his fair share of annoying. I’m not entirely convinced that Pyle gets across Kyle’s reasons for rebelling against his father, save that it’s his father. While that’s admittedly not an uncommon reason, it’s also not a compelling reason to want to read more. You get that Kyle has fallen in with the wrong crowd of kids and that he’s trying to impress them, but it’s hard to ever feel any sort of empathy for the teen. When he gets caught for stealing from Ken’s convenience store, it’s not an, "oh no" moment but rather, "it’s about time." Watching Kyle fumble to explain why he did the things that he did is at least entertaining, and says a lot about his character that on some level he can’t even come up with a good reason for why he thought stealing was all right.

The one aspect of Kyle’s story that I thought did work was his protecting Frank. While the plot line of Frank’s father being abusive feels in some ways glossed over, it’s Kyle’s understanding that ratting out Frank (even though it would have helped Kyle) would have been a bad thing was the one element that kept me reading about Kyle. It’s the first glimmer that Kyle isn’t completely bad, and the saving grace for his story. The art for Kyle’s story is done in a more traditional art style, with simple lines and a blue shading. It’s not the most elaborate style, but it works; the characters are sketched out well if simply, and there’s more emotion in those characters than you’d have otherwise expected.

The one aspect of Kyle’s story that I thought did work was his protecting Frank. While the plot line of Frank’s father being abusive feels in some ways glossed over, it’s Kyle’s understanding that ratting out Frank (even though it would have helped Kyle) would have been a bad thing was the one element that kept me reading about Kyle. It’s the first glimmer that Kyle isn’t completely bad, and the saving grace for his story. The art for Kyle’s story is done in a more traditional art style, with simple lines and a blue shading. It’s not the most elaborate style, but it works; the characters are sketched out well if simply, and there’s more emotion in those characters than you’d have otherwise expected.

I’m not convinced that the two stories ever dovetail into one another like Pyle clearly hoped; aside from Ken being in both of them, the connection isn’t quite there, another potential problem with the split-narrative. Placed side-by-side, we’ve definitely got a superior half rising up. But if we’d just gotten a graphic novel about Kyle’s life, would it be good? Possibly. It runs the problem of having a slightly stupid main character, but I can see it working, especially if the extra space had been used to flesh out Kyle some more. Take What You Can Carry is a flawed book, but I think that’s ultimately because of the 1941 storyline being so much better. Still, the pieces that do work in Take What You Can Carry are enough to make me want to see more from Pyle, and ultimately glad I read the book. It’s not a bad book, but it makes you wish that it had come together just a bit more seamlessly.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com | Powell’s Books