By Yoshihiro Tatsumi

By Yoshihiro Tatsumi

856 pages, black and white

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

I really have to commend Drawn & Quarterly for bringing Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s comics into English. They’ve already released three collections of his short stories, ones which reek of discomfort and alienation among every day, real people. I was a little wary, though, when I heard that their next Tatsumi project was an autobiography that ran over 800 pages long and only tackled a small fraction of his life. Could Tatsumi really have that much to say? As it turned out, I was very wrong for doubting; A Drifting Life may be set in the 1940s and 1950s, but it has quite a bit to say about here and now.

Hiroshi Katsumi was only ten years old when World War II came to a close with the surrender of Emperor Hirohito of Japan to the Allied Forces of the West. Three years later, Japan was only starting to really recover, and it was then in the city of Osaka that Hiroshi began to realize his dreams of becoming a comic creator. Manga was thought of primarily for children, with four-panel gag comics ruling the medium. As Hiroshi began to learn about creators who were trying something more, though, his own ambitions grew. But would manga ever be able to gain respect among the country at large? Or was he wasting his time and tying his future into a series of doomed publishers that overstepped their bounds?

Hiroshi Katsumi was only ten years old when World War II came to a close with the surrender of Emperor Hirohito of Japan to the Allied Forces of the West. Three years later, Japan was only starting to really recover, and it was then in the city of Osaka that Hiroshi began to realize his dreams of becoming a comic creator. Manga was thought of primarily for children, with four-panel gag comics ruling the medium. As Hiroshi began to learn about creators who were trying something more, though, his own ambitions grew. But would manga ever be able to gain respect among the country at large? Or was he wasting his time and tying his future into a series of doomed publishers that overstepped their bounds?

Japan is these days often held up as the fantasy land of comics, one where everyone reads manga, where subjects like romance, cooking, or sports thrive just as much as action adventure and super-powers. It’s a bit of an eye-opening experience, as a result, to jump back some sixty years and learn that it most certainly wasn’t always that way. So much of what Tatsumi’s alter-ego Hiroshi Katsumi goes through in the pages of A Drifting Life rings very true for the North American comics medium of today. Family groups denouncing any comics that are aimed at older readers, fights over the name of the medium, struggles for creators to tackle subjects they want even as the market asks for something different, publishers trying to tie down talent in exclusives solely to deprive the competition—it’s simultaneously distressing and exciting to see that all of this happened decades ago in a country that now has such a rich and varied comic scene.

Hiroshi’s life, with all of this publishing history as a backdrop, still comes out as something interesting and well worth reading. Hiroshi’s love/hate relationship with his older brother Okimasa comes across so believable that you almost feel like you’re actually sitting alongside Tatsumi’s early life as a spectator. What I found myself enthralled with was the no excuses way in which Tatsumi writes the scenes with Okimasa. We learn about Okimasa’s chronic illnesses early on, but from there we see them alternately be friends and enemies with no rhyme or reason, just like how siblings all over the world interact. There would certainly be a temptation for Tatsumi to go back and try and add in interpretations of what may or may not have gone through Okimasa’s head at the time, but instead it’s all presented in stark black and white; this is how it happened, this is how he reacted, period.

Hiroshi’s life, with all of this publishing history as a backdrop, still comes out as something interesting and well worth reading. Hiroshi’s love/hate relationship with his older brother Okimasa comes across so believable that you almost feel like you’re actually sitting alongside Tatsumi’s early life as a spectator. What I found myself enthralled with was the no excuses way in which Tatsumi writes the scenes with Okimasa. We learn about Okimasa’s chronic illnesses early on, but from there we see them alternately be friends and enemies with no rhyme or reason, just like how siblings all over the world interact. There would certainly be a temptation for Tatsumi to go back and try and add in interpretations of what may or may not have gone through Okimasa’s head at the time, but instead it’s all presented in stark black and white; this is how it happened, this is how he reacted, period.

The character of Hiroshi is by no means an angel the whole way through A Drifting Life, for that matter. While Hiroshi is our hero and protagonist, for every victory he has, there are just as many mistakes and bad decisions that play out. A Drifting Life is not only about the maturation of the comics market, but of Hiroshi as well, both struggling towards adulthood. Hiroshi’s naivety towards so many things in life—business, friends, women—is painfully awkward to read about at times as he seems to continually encounter something he knows nothing about. It’s a relief to see him slowly learn how the world really works, even if only to then find a new obstacle in his path moments later. Then again, that’s also true of the manga movement here. It’s fascinating to read about all of these different publishers struggle to find that golden ticket to success, and see all of the different publishing attempts that unfold over the years. So many of them, like the monthly hardcover anthologies, seem like such a pie in the sky dream even now that it’s hard to imagine another country attempting to build a publishing empire on these formats half a century ago. People who are savvy with understanding today’s comic market will be hard-pressed to not mentally insert contemporary publishing companies’s names on top of the ones that exist in A Drifting Life, and it’s a fun little mental game to play among one’s self.

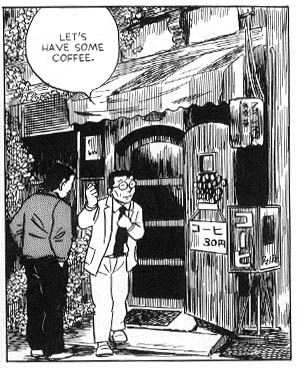

The art in A Drifting Life is slightly more varied than what I’ve seen from Tatsumi in the past, perhaps because everyone here is based off of real people. While a lot of the secondary characters fall into Tatsumi’s trap of coming out of the same mold as one another, overall I was pleased to see how much stronger the art in A Drifting Life was in comparison to his short story collections. His characters are still wonderfully awkward and gawky, and Hiroshi and Okimasa in particular are wonderfully expressive; just looking at how Okimasa is drawn over the years is fascinating because he’s always clearly the same person even though Tatsumi is able to draw him looking both villainous and friendly in ways that transform his entire face. I also really have to give Tatsumi credit for how he draws Japan in the 1940s and 1950s; so much of the story comes to life in the way that he sketches the buildings and streets of Osaka and Tokyo. Between the drawings and the little details in the story about living in that time period (the scarcity of television, the dependence on telegrams rather than phone calls even in the late ’50s), one almost feels at times like this isn’t so much an autobiography but rather a guidebook for time-travelers heading to 1950s Japan.

A Drifting Life is ultimately an enthralling book, in how it manages to speak not only of a world half a century ago but also towards today’s comic market. It’s almost painful when the book ends in 1959, with only a brief epilogue set in recent times that is painful to read—both in what is said about Hiroshi in his older age, as well as what isn’t said about the unchronicled years. I never would have predicted that after reading over 800 pages of Tatsumi’s life, I’d be hoping for another volume down the road, but that’s exactly the feeling that A Drifting Life evoked in me. If only all autobiographies were this engrossingly good. This is a book for the ages.

Purchase Link: Amazon.com