By Yoshihiro Tatsumi

By Yoshihiro Tatsumi

224 pages, black and white

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

While cleaning house, I recently uncovered a copy of Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s Abandon the Old in Tokyo. I’d read his first collection in English, The Push Man and Other Stories, and thought it was good enough to buy the second one. And then, somehow, I’d lost and forgotten about the book. Determined to read the book that I’d misplaced for so long, I sat down and started reading it—and couldn’t stop until I was done. I certainly won’t be misplacing Tatsumi’s books again.

The back cover copy of Abandon the Old in Tokyo says that Tatsumi tells the private lives of every day people, and that’s a good a description as any. If there’s an additional thread or theme to be found here, I’d say it would be discomfort and alienation. All of Tatsumi’s protagonists don’t seem to fit into the world around them, no matter how hard they try. That’s certainly true in the titular story of the book, as Kenichi tries to juggle the demands of his aged mother as well as his fiancée. Seeing him unable to really cope with either of their requests makes Kenichi come across not as someone being oppressed, but more of a sad sack figure, pathetic and pitiable.

It’s even more painfully apparent in “Beloved Monkey”, one of the stranger stories in the collection as a factory worker in Ueno tries to find a connection of any sort in his life. His pet monkey, the woman he met at the zoo, even the city itself are all things that the nameless mans reaches out to, even as all of his plans fall apart. Watching his attempts to change his life make the reader cringe, because his ideas almost always come across immediately as ill-thought and not sensible. Even as he tries to make things better, you can see disaster on the horizon. The story itself ends abruptly, almost as if it’s missing a page at the end. It feels almost like the perfect end to the story; not only would seeing any more of his life unraveling come across as painful, but the strange, almost unfinished story fits his life in general.

Some stories have protagonists easier to empathize with than others. “Occupied” is easily the most so, with Mr. Shinakawa’s plight of no longer being wanted to create children’s comics a legitimate one. His naiveté at some of the seedier elements in life is a little sad, but at the same time it’s also part of his own growth in the story, discovering new sources of inspiration. “The Washer” is the sort of story that seems to fall into the “really pathetic main character” category at first, but the more I saw of the window washer’s life and how he deals with his job and his daughter, the more I began to really appreciate him. He’s not perfect, he’s a little too reserved when he needs to speak up (no doubt in part thanks to the cultural differences between Japan in 1970, and now), but by the end of the story I had to say that I found myself liking him a lot. Tatsumi’s story “The Hole” and its strange revenge fantasy doesn’t seem to really fit with the others in places; the protagonist isn’t really who you think it is at first, and while she’s a pitiable person, I had to admit that when it was over I found myself unable to love or hate her. Her actions are questionable at best when it comes to morality, but at the same time Tatsumi does such a good job of getting inside her head that you find yourself somehow giving a pass to someone who perhaps doesn’t deserve one.

Some stories have protagonists easier to empathize with than others. “Occupied” is easily the most so, with Mr. Shinakawa’s plight of no longer being wanted to create children’s comics a legitimate one. His naiveté at some of the seedier elements in life is a little sad, but at the same time it’s also part of his own growth in the story, discovering new sources of inspiration. “The Washer” is the sort of story that seems to fall into the “really pathetic main character” category at first, but the more I saw of the window washer’s life and how he deals with his job and his daughter, the more I began to really appreciate him. He’s not perfect, he’s a little too reserved when he needs to speak up (no doubt in part thanks to the cultural differences between Japan in 1970, and now), but by the end of the story I had to say that I found myself liking him a lot. Tatsumi’s story “The Hole” and its strange revenge fantasy doesn’t seem to really fit with the others in places; the protagonist isn’t really who you think it is at first, and while she’s a pitiable person, I had to admit that when it was over I found myself unable to love or hate her. Her actions are questionable at best when it comes to morality, but at the same time Tatsumi does such a good job of getting inside her head that you find yourself somehow giving a pass to someone who perhaps doesn’t deserve one.

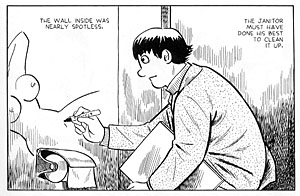

If there’s one weak spot in Abandon the Old in Tokyo, it’s certainly Tatsumi’s art. He’s not a bad artist, but he definitely has real limitations. Most of his characters fall into a standard male or female look; while it works on the idea of all of these people being a sort of “everyman” character, it’s rather distracting seeing the stories collected together, with almost all of the main characters looking like each other. I don’t think it’s any small coincidence that Mr. Yamanuki in “Unpaid”, the one male character to look radically different from the other men in the book, is easily the most visually memorable. It’s in “Unpaid” that Tatsumi’s art is at its strongest, not only in terms of different looking characters but also in how Tatsumi is able to depict an incredibly disturbing scene without showing any of the details of the act in question. Instead, Tatsumi just shows the edges of the scene, getting close enough that the movement and motions are enough to let you understand what’s happening, but mercifully staying clear of the center of the event itself.

If there’s one weak spot in Abandon the Old in Tokyo, it’s certainly Tatsumi’s art. He’s not a bad artist, but he definitely has real limitations. Most of his characters fall into a standard male or female look; while it works on the idea of all of these people being a sort of “everyman” character, it’s rather distracting seeing the stories collected together, with almost all of the main characters looking like each other. I don’t think it’s any small coincidence that Mr. Yamanuki in “Unpaid”, the one male character to look radically different from the other men in the book, is easily the most visually memorable. It’s in “Unpaid” that Tatsumi’s art is at its strongest, not only in terms of different looking characters but also in how Tatsumi is able to depict an incredibly disturbing scene without showing any of the details of the act in question. Instead, Tatsumi just shows the edges of the scene, getting close enough that the movement and motions are enough to let you understand what’s happening, but mercifully staying clear of the center of the event itself.

A third volume of Tatsumi’s stories is due out shortly from Drawn & Quarterly, and after reading Abandon the Old in Tokyo, I’ve promised myself that as soon as I get it, I won’t lose it for months. Disturbing and creepy in places, Tatsumi’s Abandon the Old in Tokyo is the kind of book whose stories will be hard to forget about. If you’re ready for a trip through the underbelly of humanity, look no further than Abandon the Old in Tokyo.

Purchase Links: